Exploring a code of ethics

ITI is working with Dr Joseph Lambert of the University of Cardiff to explore the potential of creating a Code of Ethics for ITI.

In November 2023 Dr Lambert ran an 'Ethics kick-off meeting' at which ITI members were invited to give their views on a range of vital questions about professional ethics. The event was attended by a small but engaged group of interested individuals and the discussion was wide ranging. Below is a summary from the discussion.

Part one: Presentation by Joseph Lambert

Ethics in translation essentially revolve around discerning right from wrong, navigating the realms of good and bad. This fundamental quandary emerges notably in the complexities faced during translation or interpretation. As we delve deeper, the spectrum of implications widens.

Ethics has been a pivotal concern for translation scholars, professionals and students for many years, though interest waxes and wanes. The topic was last discussed prominently in the 1990s but its significance has amplified of late, and it is experiencing something of a resurgence. This is evident from the surge of new books addressing this theme, including a commendable piece co-authored by Dr Mary Phelan, chair of ITIA. This resurgence is perhaps a response to the complexities of our current milieu: health, financial, and economic crises alongside seismic technological advancements.

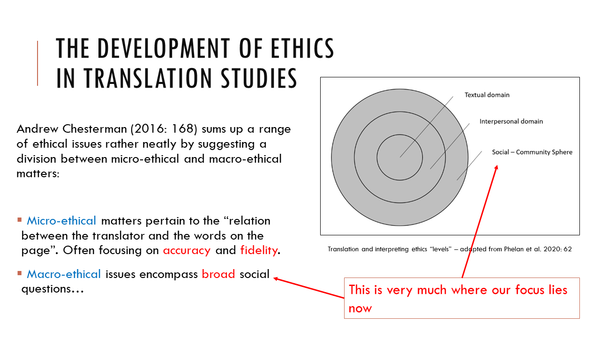

However, to simplify this expansive territory, we can focus on the evolution of ethics within translation studies, as depicted by two illustrative concepts. Andrew Chesterman delineates micro ethical issues and macro ethical concerns. Visualized on the right side of our slide, this representation, inspired by Mary Phelan’s work, vividly portrays the nucleus of textual ethics expanding into broader realms. Micro ethics, at the centre of this circle, scrutinises the translator’s relationship with the text, evoking questions about accuracy and fidelity.

However, it has become evident that merely focusing on the text isn’t sufficient. We now acknowledge the involvement of various other factors, encapsulated in the middle and outer circles of the illustration. These domains include interpersonal interactions, expanding further to encompass societal implications. The macro ethical considerations encompass a vast array of constantly evolving concerns, with new facets emerging over time.

In exploring this broad spectrum, we encounter traditional ethical concepts such as neutrality and fidelity. These are recurrent terms in ethical codes, accompanied by discussions on personal versus professional ethics, confidentiality, and conflicts of interest. Contemporary considerations encompass finance, technological impacts, issues of representation, ethical stress, and self-care among translators and interpreters. Additionally, individual and societal imperatives to address the climate crisis are gaining traction, which prompts questions about the role of the translator in a global setting and our impact beyond the confines of our translation work.

Returning to the way that ethics are discussed within the translation profession, one key area where ethics invariably emerges is within ethical codes. These codes, sometimes also known as codes of conduct or professional ethics, exist ubiquitously across various languages, cultures, and practice domains. Intended as guiding principles, these codes serve as benchmarks for translators and interpreters, contributing to the profession’s credibility and trustworthiness.

But, before delving into the specific nature of these documents, it’s essential to highlight a semantic distinction with implications for our continuing discussions about the role of a code of ethics for ITI. Often, the terms “code of ethics” and “code of conduct” are used interchangeably in professional circles. However, their nuances hold significance, mirroring the micro and macro ethical dichotomy already mentioned.

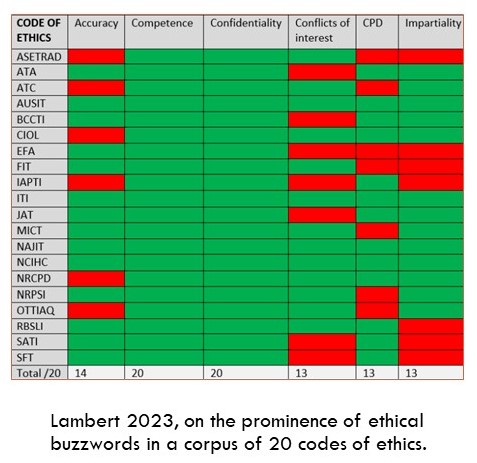

Usually, “codes of ethics” encapsulate the broader philosophical vision guiding decision-making, while “codes of conduct” addresses the micro-level, detailing specific expected behaviours and setting enforceable rules. In both cases they are mostly institutionally founded and are well-established. They also consistently echo eight common principles: accuracy, competence, confidentiality, conflicts of interest, continuous professional development, impartiality, integrity, and role boundaries. However, upon closer examination, various deficiencies come to the fore with certain limitations and shortcomings that warrant attention.

I would argue that the scope of these codes often falls short, with glaring omissions such as technology, rates of pay, data privacy, bias, environmental sustainability, and inclusivity. Furthermore, the enforcement mechanisms within these documents are often ineffectual, raising questions about their practical application and efficacy. Additionally, conflicts arise within the codes themselves, demanding impartiality while expecting advocacy, leading to interpretational challenges and ambiguity in implementation.

In conclusion, while these codes encapsulate foundational ethical principles, their static nature fails to accommodate the evolving complexities and considerations prevalent in the contemporary translation landscape. As ITI embarks on its collaborative discussions in the hope of creating a code of ethics that is comprehensive, accessible, and capable of implementation we need to maintain a realistic expectation about what can be achieved. Our ultimate goal is to better encapsulate the core ethos of our profession in a way that responds dynamically to the ever-evolving ethical challenges and wider societal concerns.

Part two: Discussion

Defining professionalism in translation and interpreting

The discussion began by exploring the essence of professionalism within the realms of translation and interpreting. Participants shared their varied backgrounds and experiences of entering the translation and interpreting professions. Some had transitioned from different careers into language services and emphasised the importance of professionals being able to recognise their capabilities and limitations. Participants also highlighted the intricacies involved in defining professionalism in our field, emphasising its multifaceted nature and complexities.

Professionalism was perceived as involving earning a livelihood from translation or interpreting while embracing a sense of responsibility. There was a clear sense that professionals take full responsibility for their work, understanding and mitigating the risks associated with their expertise, akin to other established professions like law and medicine.

Continuous learning and professional development were also seen as crucial elements of professionalism. Evidence of commitment to ongoing education, staying up to date, and adhering to ethical standards were stressed throughout the conversation.

While being a member of a professional association and therefore signing up to a code of conduct was seen as important for professional recognition, it was acknowledged that membership of associations such as ITI isn’t mandatory to be considered a professional in language services. Participants lamented the lack of broader recognition and regulation within the translation and interpreting professions, leading to the constant need to assert professionalism in a competitive market crowded with unqualified practitioners.

Comparisons were again drawn between translation and interpreting and other established professions like medicine and law, where the distinction between professional and non-professional practitioners is defined and managed by stringent regulations.

Examples of ethical dilemmas

Participants shared instances where adherence to codes of conduct or ethics posed challenges. These included dealing with complexities in translation contracts, and scenarios where understanding the cultural background of the target text brought added knowledge of ethical issues unknown to the client. The need to define professional boundaries when interpreting medical reports or legal documents was also mentioned.

The conversation then delved deeper into various ethical challenges faced by professionals:

- Role boundaries and added-value services

- Quality concerns with machine translation

- Accountability, risk, and liability

- Visibility and recognition

- Deadline pressures

- Fair freelance rates

- Training and continuing professional development

- Multiplicity of sometimes conflicting codes of conduct and ethics.

The discussion suggested that there was an appetite to develop ethical guidelines that encompass the key issues of fair compensation, accountability, quality standards, and professional development. However, participants also acknowledged the diverse challenges faced by both newcomers and seasoned professionals in translation and interpreting.

Towards an ethical framework

Participants discussed potential actions that could shape the development of an ethical framework for ITI within the broader translation and interpreting professions. Suggestions included:

- Surveying ITI members to gather further views about the various elements that might make up a future ethical framework

- Collaborating with other organisations to gather more diverse perspectives

- Developing video presentations or webinars to encourage members to engage with the existing ITI Code of Conduct

- Emphasising the merits of continuing professional development and self-reflection akin to practices in other professions like medicine.

The conversation concluded with an emphasis on putting in place an iterative process that will deliver an ethical framework for ITI members that is aligned with the evolving needs of the profession. ITI Chief Executive Sara Crofts welcomed this approach and expressed her willingness to consider additional feedback and ideas, reinforcing the message that the kick-off meeting was only the start of the process. She also thanked Dr Joseph Lambert for sharing his thoughts and guiding the discussion.