In his shoes

Tony McNicol outlines some of the unexpected challenges he encountered in translating the memoir of a very different life from his own

The joy of being a translator, particularly for a generalist like me, is never knowing what might be waiting in your morning inbox. A couple of years ago it was an email from a Japanese publisher about the memoir of a Japanese Buddhist monk, make-up artist, and LGBTQ activist called Kodo Nishimura. The project turned out to be quite as unique as the memoir’s author. What’s more, as well as linguistic challenges, it prompted some tricky and uncomfortable questions of authenticity and identity.

Like many Japanese monks, Kodo was effectively born into the job. Both his parents were priests, and he grew up in his family’s Tokyo temple. But at school he struggled painfully with his sexuality and gender identity, experiencing discrimination and isolation. As soon as he was old enough, he moved to the US, where he studied art, came out to first friends then family, and became a successful make-up artist. (Kodo doesn’t identify as either male or female but does use the pronouns he/him.)

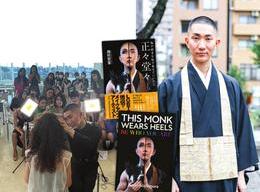

Eventually however, Kodo decided to return to Japan and follow in his parents’ footsteps. He completed the arduous training to become a Pure Land Buddhist monk and became a high-profile LGBTQ activist. He has since featured widely in Japanese and foreign media, including being named as a Next Generation Leader by Time magazine and appearing on the Netflix show Queer Eye: We’re in Japan! I was asked to translate his memoir, now titled in English as This Monk Wears Heels – Be Who You Are, and published in February 2022 by Watkins Media in the UK and Penguin Random House in the US.

The emperor’s pronoun

The first challenge I faced as translator was the highly gendered nature of the Japanese language. Japanese men and women often use distinct words and grammatical structure particularly when speaking. Compared to English, even the pitch of one’s voice tends to be shifted high or low to signify ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’. (This can end up being a significant problem if you learn Japanese from someone of a different gender and instinctively copy what you hear.) Kodo’s memoir was written in quite a chatty way, and his voice was slightly feminine. How to replicate that in English? This brought up the thorny issue of authenticity that I will come to later.

Not wanting to use an ‘I’ that was distinctly male or female, he resorted to a polite neutral ‘I’, despite fearing it would make him sound somewhat formal and distant.

Another challenge was the Buddhist terminology. I’m not a Buddhist scholar, and frankly, here unwary translators rush in where Bodhisattvas fear to tread. One problem is that an English text on Japanese Buddhism could easily include Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, and English words. And some terms have equivalents in all the languages! For example, should the Buddhist goddess/god of mercy be referred to as the Chinese Guanyin, the Sanskrit Avalokiteśvara or the Japanese Kannon? (The last is perhaps easiest to remember because it was the inspiration for the camera company Canon.) Meanwhile, the rules about romanisation are more than a little confusing. The Wikipedia page for a famous seventh-century Chinese monk called Xuanzang lists over 50 different versions.

Issues of identity and authenticity

For monk, make-up artist and LGBTQ activist Kodo Nishimura, being who he is means being someone different from who he was brought up to be.

A more secular translation challenge was the astute advice on fashion and make-up that Kodo shares in his book. This became a lesson in researching something I know very little about. YouTube tutorials, and occasionally my wife, saved the day. Unfortunately, I didn’t try out any of Kodo’s make-up advice but I did successfully apply a key fashion tip. In a nutshell, Kodo says to keep only the clothes that you like, wear regularly, and are sure really suit you. Throw everything else away. Try it. It works!

More seriously, I want to address a difficult question this project threw up, one related to identity and authenticity. Namely, was the fact that I don’t myself identify as LGBTQ relevant to translating the often raw and personal lived experience of someone who is LGBTQ?

As I was writing this, I came across a Guardian article by the Jewish comedian and author David Baddiel. It was about acting and authenticity, and the growing consensus that members of marginalised groups should be played by actual members of those groups (although his key point was that this consensus tends not to extend to Jews). Baddiel mentioned the need to correct the historical underrepresentation of minorities in the performing arts and to avoid offensive caricature by actors, of which ‘blackface’ is the most notorious example. Meanwhile, Baddiel reiterated the argument for authenticity in acting. ‘The deep truth of any marginalised identity is only available to those who live that identity,’ he wrote.

Translators do not ‘play’ roles, but we do channel identity and experience. Do we also need to consider these issues?

Representation without caricature

The first thing to say is that marginalised groups are clearly underrepresented in our profession. It is an important topic covered by Ruth Partington and Tayo Ademolu in this issue and other writers in previous issues.

How about conveying ‘deep truth’? Perhaps many translators would instinctively feel that expressing truth is down to the original writer and that their job is only to ‘translate’. Yet, as a reader of novels and memoirs myself, I know that fully understanding meaning sometimes requires empathy. Is shared experience sometimes a prerequisite for that?

So, am I an appropriate person to translate a memoir by someone who is LGBTQ? I would like to say I asked myself that question immediately on being approached by the publisher. But my instant reaction was to say ‘yes’ to a great project that had landed in my lap. It was only during the translation process that these issues came into focus.

In any case I can’t help wondering whether, had I turned the publisher down and suggested they seek an LGBTQ translator, they would have taken my advice or just emailed the next person on their list. Besides, if they had found an ‘LGBTQ translator’, would that person have had exactly the right lived experience to translate the book? Nishimura himself says that none of the identities denoted by LGBTQ perfectly matches his own.

I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I did end up translating the book. And I do know that the job of a translator involves not just translating words, but culture and experience. Arguably, the more alien to each other those cultures and experiences, the more our skill as translators is needed. In other words, my reason – perhaps a selfish one – for translating the book was that Kodo is so different from me.

There is a great early-reader quote on the cover of the proof copy I have: ‘They say to really know someone you must walk a mile in their shoes. Reading his story felt like I had popped on a pair of heels, and it was fabulous.’ While I haven’t shared the often painful lived experience that Nishimura describes so movingly, translating his words into English did at least help me learn, understand and empathise a little. I hope I have helped readers of the translation do the same.

Never miss another Bulletin article

If you would like to read more features and articles on a wide variety of subjects relating to all aspects of the translation and interpreting industry, subscribe to ITI Bulletin. Alternatively, join ITI and get a free subscription included in your membership.