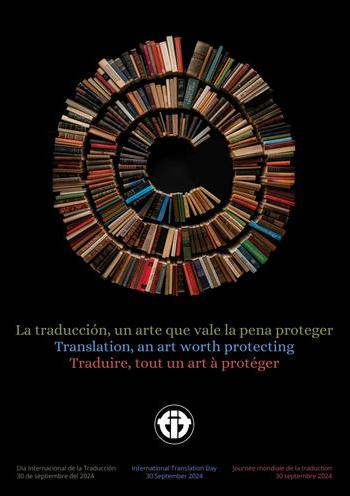

Translation, an art worth protecting

This year’s International Translation Day theme embraces the recognition of translations as original creative works in their own right, owed the benefit of copyright protection.

"As the creators of derivative works, translators have fought to protect their moral rights to be credited for their translation work, control any changes to that work, and receive appropriate remuneration. Protecting these simple things will ensure a sustainable future for translation professionals and the historic art of translation itself.

Copyright-related issues extend far into all areas of the profession, including the use of translations in the cultural sector, literary translation, publishing and legal translation. With the development of AI and the expansion of the digital sphere, the implications of copyright for translators, interpreters and terminologists have increased exponentially and attribution is increasingly crucial. In addition to allowing translators to receive recognition for their efforts, it clearly signals the source of a text, identifying it as human rather than AI generated content."

https://en.fit-ift.org/international-translation-day/

In this article Sue Leschen explains the fundamentals of copyright and the rights it grants copyright owners.

Understanding copyright

Copyright is a form of Intellectual Property (IP). IP is intangible property which automatically exists from the time of the creation of the work by humans (or these days by AI?). IP grants the copyright owner various exclusive rights. Other forms of IP include patents, trademarks and trade secrets which also grant exclusive rights: to make, use or sell an invention (patents/ Dyson hoovers), to protect a brand name or logo (trademarks/ McDonald’s Golden Arches logo) to protect business know – how (trade secrets/ ingredients in Coca Cola).

Copyright holders have exclusive rights to grant permission to others to copy original created works – but usually only grant this right for a limited time. Copyright also seeks to prevent unauthorised copying. Creators of original works are thus in theory at least (it may be difficult to police!) protected by copyright which grants them two main categories of exclusive rights:

- Economic rights – commercial benefits when they either license others to use their work or sell their rights to others for a fee.

- Moral rights – these protect the non-economic interests of the creator who has invested time and thought in their creation. The creator can keep (or waive) their rights, for example the right to be identified as the author of the work and/ or the right to object to how their work has been presented where there may be reputational damage.

The creator may or may not be the copyright holder, for example if they are an employee who created the work in the course of their employment because here copyright belongs to their employer.

Copyright protection

Copyright can protect numerous and varied types of IP such as website content, data bases, audio and video recordings, personal correspondence and photos but can’t protect business names and/ or logos. In England and Wales case law has consistently held that works need not be of great aesthetic or intellectual value to warrant copyright protection – they simply need to be original works.

Talking of translations, the default position for translators is that they usually retain the copyright in their translation unless there is an agreement with the client to the contrary.

The creator of an original work has the exclusive right to authorise various acts in relation to their work such as copying, adaptation, audio and/ or visual public performances, either paid or unpaid distribution, renting or lending. In England and Wales (and in most countries) copyright of written works lasts a minimum of life plus 70 years (and 25 years for photos).

“Copying” an original work can include photocopying, making recordings and even reproducing a printed page by handwriting it or vice versa. “Distributing” an original work can include downloading a document for public consumption while “communication” of an original work could include uploading a translation to the internet and “adaptation” of an original work can include translations into different languages.

Talking of translations, the default position for translators is that they usually retain the copyright in their translation unless there is an agreement with the client to the contrary.

In England and Wales, notification to third parties that work is copyrighted is not legally obligatory – there is no legal requirement to formally register copyright anywhere. This is in contrast to patents and trademarks which do have to be registered. However, the © symbol clearly indicates to others that copyright exists and that the copyright holder may exert their rights if there is a breach.

What to do when copyright is breached

As regards breaches of copyright of all of the work or perhaps a substantial part of it, the copyright holder should act quickly to protect their business reputation and integrity. A range of options are available such as sending “a cease and desist” letter requesting the other party to stop the breach by a certain time, not to breach in the future and warning them of potential legal proceedings if the breach is ignored.

Most contracts for services will include a voluntary confidential mediation clause where an impartial mediator will try to assist the parties to find common ground where there has been a breach (without the need for formal court proceedings). Here the parties’ final agreement, while not legally binding, can be enforced as a contract. Alternatively, the parties could take advantage of a voluntary arbitration clause in their contract and submit their dispute to an independent arbitrator whose decision will be legally binding. Like mediation this is a quicker and cheaper process than going to court. If necessary, commencing court proceedings can be a last resort but it is only worth doing this if it is known / obvious that copyright has been breached, the extent of the breach or even who breached first – again proof may be problematic! Where copyrighted material has been sold, the buyers may or may not be complicit in the breach so their cooperation is not automatically guaranteed. As with all litigation, winning is never guaranteed and there may be a costs issue for the loser.

In England and Wales, both civil and/ or criminal proceedings can be brought. In the civil court the copyright holder can apply for damages (financial compensation) and/ or injunctions (court orders to stop the breach) within the limitation period (6 years from the breach). Depending on the amount claimed, claims can be brought in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) in either the Small Claims Court, the County Court or the High Court.

Alternatively, criminal proceedings can be brought in the Magistrates Court by the Crown Prosecution Service or Trading Standards (whereas individuals can bring private prosecutions under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (CDPA) 1985.) Private prosecutions are rare as they can cost as much as £8,500 but may be worth pursuing if breaches are on an industrial scale. Penalties and forfeitures of illicit recordings and copies can be ordered under the Copyright and Trademark (Offences and Enforcement ) Act 2002.

If in doubt about copyright issues, free advice can be obtained from the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) at [email protected] and also from our Professional Indemnity Insurers’ legal advice departments.

Defences to breaches of copyright are covered by certain exceptions in CDPA, such as the material in question was used for research and private study or education and training and/ or the copyright holder granted an implicit or explicit licence to use their work.

It should be borne in mind that where copyright protection exists in England and Wales, that it won’t cover breaches occurring abroad – unless an international agreement exists such as the Berne Convention on literary and artistic works.

Some general rules (in the absence of any agreements to the contrary to transfer copyright on delivery or payment for the translation) are that copyright in the original work belongs to the creator or, if not, to the company which commissioned the work by them; translations of source language documents are considered to be “derivative works” (derivative because their very existence depends on the existing work) which are protected by the same copyright as that of the original work and are owned and controlled by whoever commissioned them. Some scenarios may involve several different copyright holders such as for the text in the document, the translation of the text and the illustrations in the text.

Copyright and remote interpreters

Particular problems for Remote Interpreters (RIs) as regards recordings and screen shots by their clients of their audio and visual images are that our permission to use the latter may never be requested, may be sought during the event being recorded, may be unpaid or poorly paid. Also RIs may have been supplied with copyrighted materials to assist them to prepare for the assignment which their client has no right to use. Some clients may agree to RIs retaining copyright of their images but may request royalty-free licences to distribute them to their end clients. Of particular concern now is that AI can clone the human voice……

Talking of AI, there is growing evidence that our translations and visual and audio recordings are now being used to train AI. As AI generated content may closely resemble our original work it may be difficult to spot if and where it has been used. The current legal situation is unclear but an EU AI Act is now on the horizon which will require AI companies to get authorisation to use copyrighted content. While a balance is needed between innovation and protection, it is clear that AI challenges the traditional view, namely that only human-created work merits copyright protection.

Protecting ourselves

We need to be proactive in protecting our professional reputations and businesses when negotiating jobs with potential clients which potentially involve our copyright – we should be asking pertinent questions such as:

- Who will see/ hear our work?

- Where are they?

- How often will our work be used? If use is ongoing, will royalties be paid?

- Can we review recordings before transfer of our copyright?

- Which parts of our work will be used? All of it or just specific parts?

- Will it be amended after transfer? If so, our written permission must be sought prior to transfer without which we will not be liable for any consequences.

Also of interest